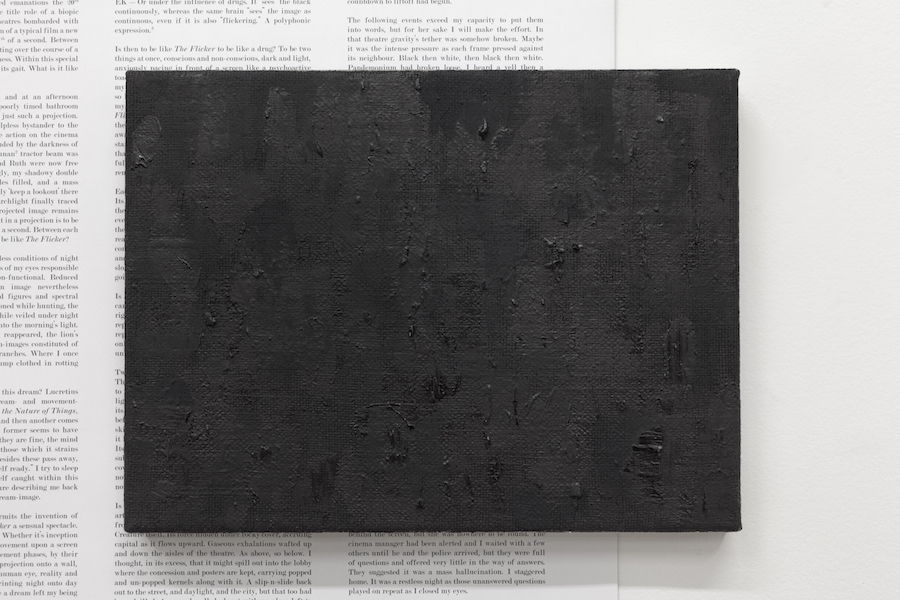

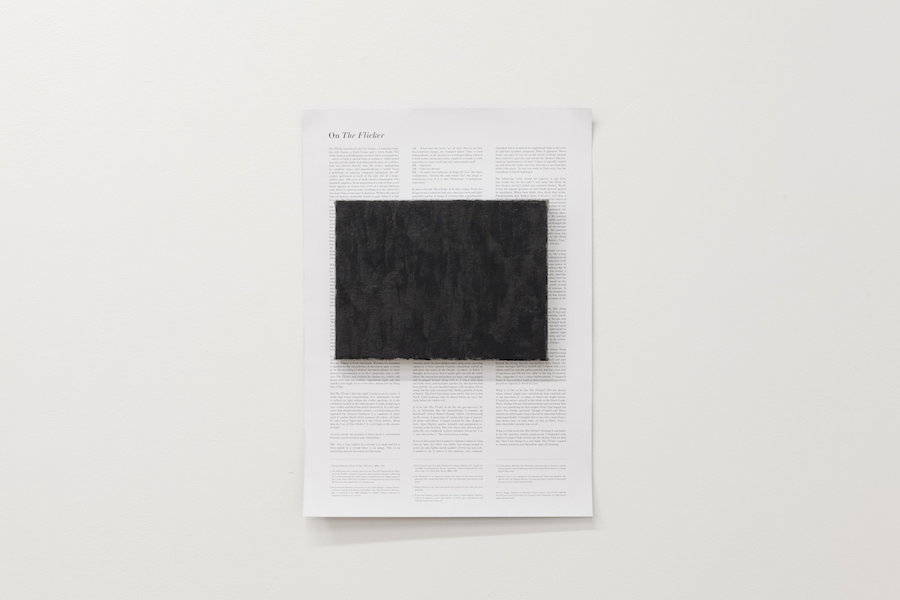

The Flicker, 2017. Suite of 24 collaborative oil paintings made with Jennifer Carvalho (each 9 x 12"), Duvetyne, resin coated popcorn, printed text

photo credit: Yuula Benevolski

On On The Flicker

1.Extramission

Driving at night, one sometimes comes across the familiar sight of an animal – a badger or raccoon, perhaps – surprised in the middle of the road by the car headlights. The animal looks up: its eyes are shining brightly. Today we know that this phenomenon, ‘eyeshine’, is a simple physiological effect. The retinas of many nocturnal animals’ eyes are backed by a reflecting layer called the Tapetum lucidum. This layer of tissue reflects visible light back through the retina, increasing the light available to the animal’s photoreceptors. This contributes to the superior night vision of some animals. Even without the tapetum, however, some light is reflected back out from the eyes. In humans this is often observed in flash photographs, where the phenomenon appears as the well-known ‘red eye’ effect.

In ancient Greece, however, eyeshine wasn’t attributed to this thin tissue behind the retina. Rather, according to Empedocles (and echoed by many others) it was evidence for a pure fire – essential to sight – that burned within the eye and shot its rays out, sun-like, to illuminate the world. Versions of this emission or extramission theory could be found in the Bhagavad-Gita, Homer, Plato, al-Kindi, Augustine, and many others, and it entailed an essential activity of movement out from the eye into the world, with all its attendant metaphysics. Euclid’s seminal Optica, written around 300 BC, was the first concentrated mathematical study of the properties of light and reflection. Although he began to question extramission theory, pointing to the seeming impossibility of being able to see stars at night immediately after opening one’s eyes (after all, how could the fire in one’s eyes travel so far into the night sky that it could reach the constellations), his mathematics in the Optica begins with a set of definitions, the first one reading, “[l]et it be assumed that the lines drawn directly from the eye pass through a space of great extent.”1

The theory persisted as the favoured model until the 1300s. By the 1700s it had all but been obliterated, and science had replaced emission with ‘intromission,’ wherein light reflects from objects into the eye, in essence reversing the direction of the ancient beam. Nonetheless, our idiomatic language maintains echoes of it: we talk of “lines of sight,” of someone having a “penetrating gaze,” of “seeing through” someone, of “shooting daggers” at a rival. Perhaps this is a legacy of the earlier beliefs, but maybe it’s also because these beliefs haven’t actually dissipated. In 2004 an article in a psychology journal noted the author’s shock that that many adults – 33% of college students according to another study – think something leaves our eyes when we look at an object.2

2. Tony Conrad’s The Flicker Aryen Hoekstra’s The Flicker

Aryen Hoekstra’s new exhibition at YYZ is not a 30-minute film from 1966 that–aside from its opening titles–consists of entirely black and white (actually clear) frames by Tony Conrad. And yet Conrad’s The Flicker serves as a structuring absence in the exhibition, being everywhere and nowhere at once. Troubling conventional centre-periphery relations, the exhibition simply banishes what one might have thought to be its focal point.

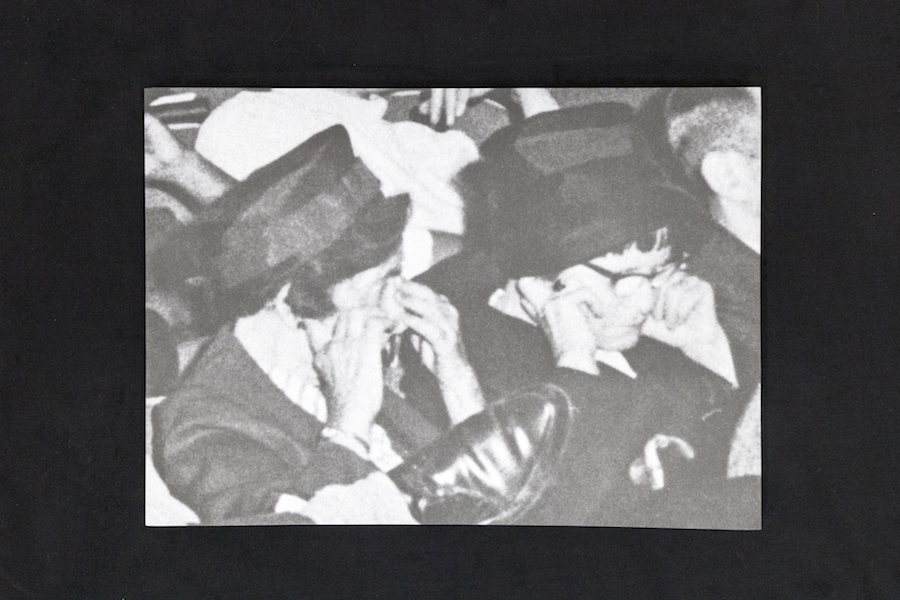

Here, instead of a stroboscopic film we find a gallery floor lined in Duvetyne (used in film and stage production), strewn with bits of popcorn. There is a stack of posters with an image of two be-hatted women, fingers in their ears, seemingly at the cinema. On the verso of this poster is a short story. And we also find a number of small black paintings that may or may not recall the uneven blackness one sees when closing one’s eyes. Yet Conrad was actively positioning The Flicker against painting: “[It] was not a recuperative exercise in structural minimalism, along the lines of the formalist works of LeWitt, Morris, Smith, Olitski, et al. If anything, it was preconceived as an assault upon that estheticism.”3 Perhaps Hoekstra’s paintings paradoxically bring us closer to the work of Conrad than one might suspect. Conrad made paintings that were not paintings.

***

Tony had some Paintings in the exhibition Über zwei Ecken/Two Degrees of Separation at Kunsthalle Wien in 2014 that I curated. These objects, however, were not what one would traditionally call ‘paintings’. They were large panes of glass, hung from the gallery ceiling with a (peep) hole cut into each of them.

My glass pieces, titled Painting, illustrate the discursive differential between physical vision and the ‘gaze.’ Here seeing is directed along two paradoxically incompatible pathways: one follows the transparency of glass; the other is the conceptual magnetism exerted upon the viewer by the presence of the hole.4

These Paintings are pronouncedly unpainted. And this is not the first time Tony has made a counterintuitive claim about an object’s membership into a category of art. In the early 1970s he made his Yellow Movies by forming rectangles out of cheap household paint on a single sheet of paper. ‘Cinematic’ and yet film-less. These were ‘movies’ in that they changed over time due the chemical effects of light on the cheap paint. Over a period of many years, the paint yellowed. This long-term, effectively infinite process defines the running time of each movie; that is, each ‘runs’ indefinitely until the paint will no longer change colour or the work is destroyed.

***

Instead of imaging (painting) what one sees when one closes one’s eyes, in Conrad’s film the flickering frames were employed to create a physiological response in the viewer’s body, in their eyes, and in their brains. This was not about representing an image, or an approximation, but actually generating one. Here the colours and movement that many of the theatre-goers reported having experienced while watching the film, emanated from inside the viewer, and were seen externally. Through The Flicker we have come back to a version of extramission-theory. “Another thing that’s elusive, but nevertheless really there, is the experience of colour. During The Flicker people see colours, even though all that’s actually on the filmstrip is a bunch of black and white frames. It fascinated me that people saw colour all the time, and not only colours, but moving colours, whirling colours.”5

***

Tony and I discussed extramission theory at length while working on his Vienna exhibition. When I told Tony that I had a degree in Classics, he realized that he didn’t have to hold back any longer, and let loose. I’ve just checked my Skype history and our conversation about this was 2:36:18 minutes long. We could have watched The Flicker five times. We emailed back and forth about it. One of the emails contained a more edited summation of how it related to his current work:

Brunelleschi’s architectural designs demanded an understanding of the rendering of three dimensions as two-dimensional diagrams or paintings. Orthographic diagrams provide one solution to this problem; projective geometry and linear perspective provide another. Reflections upon the production tactics and viewership situations involved in linear perspective paintings generated a discourse based on point of view---or in contemporary language, a discourse of the gaze.

This ‘gaze’ was a necessary antecedent to the development of classical optics, which traces light lines as transmission paths through transparent media. However, these transmission paths are not the lines of sight; “lines of sight” are a confusion that arose in Greek thought under the influence of those who imagined that sight somehow emanated from the eye or eyes of the viewer.

Just as much an unjustifiable fiction as these lines of sight is the gaze –a concept that is completely separable from the physical understanding of light ‘rays.’ The idea of ‘gaze’ is not applicable to the logic of painting or cinema in any contemporary sense. The idea that somehow a small aperture meaningfully conveys the interests and visual engagement of a viewer needs to be set aside if any coherent thought about perspective, or about the relation between viewers and cultural objects, is to develop further.6

“I watched Ad Reinhardt follow Robert Ryman follow Ad Reinhardt on the screen. A procession of a particular type of painter, all dense and obtuse.”7

Tony’s ‘paintings’ weren’t paintings, and his ‘movies’ weren’t movies (except that they were). Ari’s exhibition isn’t The Flicker, and it isn’t a recreation of watching The Flicker (except that it is).

3. Lenny Bruce

On March 31,1964, Herbert G. Ruhe, a former CIA agent and then license inspector for the City of New York, had been sent by the Manhattan District Attorney to covertly attended a performance by Lenny Bruce at the Café Au Go Go in Greenwich Village. This performance, along with others from the same run, would form the basis for a court battle as obscenity chargers were brought against Bruce. According to Richard Kuh, the man who would later lead the prosecution against Bruce, Ruhe was blessed with a "phenomenally well-developed memory." As Bruce performed, Ruhe busily scribbled down terms including "jack me off," "nice tits," and "go come in a chicken." Ruhe added his own editorial comments, such as "philosophical claptrap on human nature." These notes, however scant, were used as prompts for Ruhe as he was asked in court to relate Bruce’s monologue to the jury. In effect, Ruhe reperformed Bruce’s act. “This guy’s bombing,” Bruce had said in a stage-whisper loud enough to be heard by the court, “and I’m going to jail for it. He’s not only getting it all wrong, but now he thinks he’s a comic. I’m going to be judged on his bad timing, his ego and his garbled language.”

Ruhe’s infamous reconstitution of the performance, his bad delivery, is a parallel kind of parafiction8 to the one we see in Hoekstra’s gestures. A monotonous and biased delivery in front of a jury, rather than a comedy act at a club, is as inaccurate to the original event as popcorn on the floor, paintings in a gallery, or a narrative that slowly introduces elements of magical realism is to the event of Conrad’s The Flicker. It is through these intentional inaccuracies that we can think of the tension between film as a reproducible object and the screening as an ephemeral event. And we can also think of the tension in the relationship between the minimalism and austerity of The Flicker and the sociality and eventfulness of its exhibition. The Flicker is a filmic experience. The Flicker is an extreme case of something true of every film: every screening is a repetition and yet also a unique performance. The attendant questions then become, what happens when the film is, in effect, a non-film? And what happens when the place where the work works is not the screen, nor the celluloid, but physically in the viewer? This makes the supposed reproducibility of the film moot. This is why, Conrad has said, “One was the way the film turns the audience into a kind of sculptural array.”9 As every audience has a different set of faces, each time it will be different, a unique sculptural array. And it is here – between film and non-film, a parafictional account of an event, and painting that is not painting – that we find Hoekstra.

Hoekstra’s The Flicker is more clearly about not reconstituting the original event more than it is about reconstituting it. It is concerned with failing to do so and/or the impossibility of recapturing that ‘original event’. This then accounts for the inaccurate or parafictional elements, like the popcorn dotting the gallery floor: it is extremely unlikely that the first major screening of The Flicker was accompanied by the theatre-goers chomping away at popcorn. This is avant-garde experimental film, not The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming (the top grossing film of 1966). None of the photographs from the first screening at the Film-Makers' Cinemathèque in New York show evidence of popcorn, nor do the more famous photographs from the Fourth New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, New York, 1966. But Hoekstra is not aiming for fidelity to an unlocatable original.

It’s not The Flicker, but it asks what is it like to be like The Flicker.

It’s not history, but can’t be called not-history.

Gareth Long, 2017

1. Euclid, “Optica”, Translated as “The Optics of Euclid” by Harry Edwin Burton, Journal of the Optical Society of America, Volume 35, no. 5, (May 1945): p. 357.

2. Stephen. L. Chew “Student Misconceptions in the Psychology Classroom,” in Essays from Excellence in Teaching Vol.4, K. Saville, T. Zinn, & V. W. Hevern (Eds.), (Society for the Teaching of Psychology: 2004), Available at http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/eit2004/index.php (retrieved April 2, 2017), pp. 11-16; Gerald A. Winer and Jane E. Cottrell, “The Odd Belief That Rays Exit the Eye during Vision” in Thinking and Seeing, Visual Metacognition in Adults and Children, Daniel T. Levin (ed.). (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2004), pp. 97-119.

3. Tony Conrad, “Is This Penny Ante or a High Stakes Game?,” in Millenium Film Journal No.43/44 (Summer/Fall2005)–Paracinema/Performance, pp. 103-105.

4. Tony Conrad, e-mail correspondence with author, November 25, 2011, subject: “Kunsthalle Wien Note for Gareth”.

5. Scott Macdonald, “Tony Conrad: On the Sixties” in A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Film Makers, (Los Angeles and Berkeley, University of California Press: 2006), p. 74.

6. Tony Conrad, e-mail correspondence with author, November 25, 2011, subject: “Kunsthalle Wien Note for Gareth”.

7. Aryen Hoekstra, "On The Flicker," text-work produced for the exhibition The Flicker, presented at YYZ Artist's Outlet, April 12 - 27, 2017.

8. I’m indebted to, and am borrowing from Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s investigation of parafiction in “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” in October, Vol. 129 (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2009), pp. 51-84. Here Lambert-Beatty distinguishes her use of ‘parafiction’ from the way it is sometimes used in Literary Studies to designate true stories told in the style of fiction.

9. Scott Macdonald, “Tony Conrad: On the Sixties,” in A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Film Makers, (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), p. 74.